In this translation, the eruption date is cited as being in August. There are other sources that put the eruption date into October (derived from the fact that fresh olives were found in some houses in Pompeii).

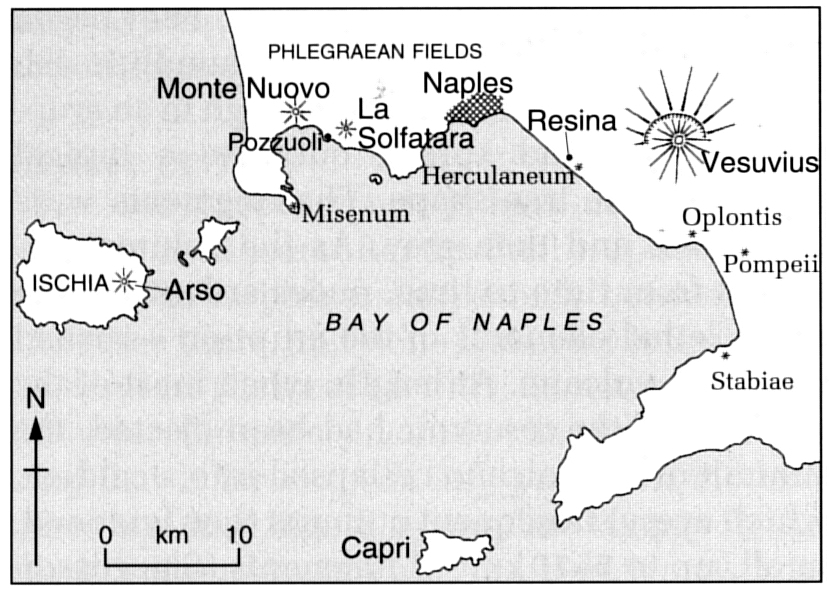

It is interesting to note that Pliny never mentioned the towns of Herculaneum (Ercolano) and Pompeii so that their existence remained unknown until the late 16th century. Excavation began in 1748. The excavated city (together with Herculaneum and a few others)are historically very significant. People fled in great haste, leaving behind valuables and items for daily use. In some buildings, paintings, mosaics and sculptures have survived, and graffity (announcements, advertizing sales, expressing personal opinion) is still visible on street walls. Sir William Hamilton, the English Ambassador to the court of Naples, witnessed eruptions between 1766 and 1794. His descriptions of the eruptions as well as the regional geology are often regarded as the first truely volcanological reports. He was also present at the excavations of Pompeii.

Source: A, Scarth and J.-C. Tanguy, "Volcanoes of Europe", 2001, Oxford University Press; ISBN: 0-19-521754-3)